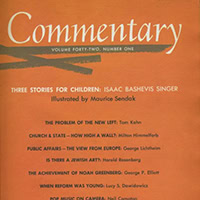

Jewish history has taught Jews to be wary of the intermingling of religious establishments and political power, so it’s understandable that American Jews instinctively safeguard the separation of church and state. But there is a wide gap between opposition to a state church and the radical separationism of the type Milton Himmelfarb criticizes in his classic 1966 essay on government support for parochial schools, “Church and State: How High a Wall?”

To Jews, Jewish separationists like to say that separationism is necessary for our safety and well-being. I think this argument is a second thought, invoked to justify a decision already taken on another ground. Those who invoke it remind me of a businessman who wants to contribute corporation money to a university or a community chest or the symphony orchestra. Possibly he wants to do it because he is a decent, generous man, but he has to justify his decency, to himself as well as to the other officers and the stockholders, by giving businesslike reasons for the contribution: it will be good for public relations, or it will help to make the environment so healthy that the corporation will be able to thrive.

There would be nothing wrong about consulting our interest when we are making up our minds whether to support governmental aid to church schools in the name of better education or to oppose it in the name of separation. If we consulted interest, we would estimate advantages and disadvantages by applying the appropriate calculus. That is how a man runs his business, or he is soon out of business. It is how Mr. McNamara chooses between missiles and manned bombers, submarines and aircraft carriers. But though I follow the Jewish discussions, I recall little that resembles a true weighing of alternatives. We prefer incantatory repetition of the dogma that separationism is our interest.

It is time we actually weighed the utility and cost of education against the utility and cost of separationism. All the evidence in America points to education, more than anything else, influencing adherence to democracy and egalitarianism. All the evidence points to Catholic parochial education having the same influence. (And all the evidence points to Catholic anti-Semitism as no greater than Protestant, and possibly less.) Something that nurtures a humane, liberal democracy is rather more important to Jews than 24-karat separationism.

…

In the political and social thought that has least to apologize for, despotism is understood to prevail when state and society are all but identical, when the map of the state can almost be superimposed on the map of society. In contrast, freedom depends on society’s having loci of interest, affection, and influence besides the state. It depends on more or less autonomous institutions mediating between the naked, atomized individual and the state or rather, keeping the individual from nakedness and atomization in the first place. In short, pluralism is necessary.

Given that a shriveling of the non-public must fatally enfeeble pluralism, especially in education; and given that the agent of that enfeeblement is the unchecked operation of economic law, the remedy is simple: check it. Let the government see that money finds its way to the nonpublic schools, so that they may continue to exist side by side with the public schools. That will strengthen pluralism, and so, freedom.

Read the whole thing at Commentary.

- Judge Matthew Solomson on Orthodox Judaism and American Public Service

- Yossi Melman on Israel’s Most Famous Spy

- J.J. Kimche on Paul Johnson’s Legacy of Philo-Semitism

- Ari Heistein on the American War on the Houthis, and the Israeli One

- Michael Doran on Donald Trump’s Middle East Policy

- Benedict Kiely on Pope Francis and the State of Jewish-Catholic Relations

- Leon Kass on How Exodus Created the Jewish National Narrative

- Dara Horn on Her New Graphic Novel

- Tevi Troy on How Republican Administrations Argue about Israel

- Micah Goodman on What He’s Learned about Israel in the Past Year-and-a-Half

- Mark Gottlieb and Anna Moreland on Judaism, Christianity, and Forgiveness

- Ronna Burger on Reading Esther as a Philosopher (Rebroadcast)

- Reihan Salam on Rebuilding Urban Conservatism

- Hussein Aboubakr Mansour on Why the End of Palestinian Nationalism Can Bring Hope to Palestinians

- David Bashevkin on Orthodox Jews and the American Religious Revival

- Diana Mara Henry and Gabriel Scheinmann on One Jew Who Fought Back against the Nazis

- Cynthia Ozick on “The Conversion of the Jews” (Rebroadcast)

- Amit Segal on Israel’s 60-Year-Old Prisoner Dilemma

- Ross Douthat and Meir Soloveichik on the State of American Belief

- Michael Doran on Jimmy Carter and the Middle East

- Brad Wilcox on Americans without Families

- Our Favorite Conversations of 2024

- Terry Glavin on Rising Anti-Semitism in Canada

- Hussein Aboubakr Mansour on the Fall of Syria and the Death of Baathism

- Bella Brannon and Benjie Katz on Anti-Semitic Employment Discrimination at UCLA

- Ari Lamm on the Biblical Meaning of Giving Thanks

- Maury Litwack on the Jewish Vote in the 2024 Elections

- Jon Levenson on Understanding the Binding of Isaac as the Bible Understands It (Rebroadcast)

- Mark Dubowitz on the Dangers of a Lame-Duck President

- Matthew Levitt on Israel’s War with Hizballah

- Meir Soloveichik on the Meaning of the Jewish Calendar

- Elliott Abrams on Whether American Jewry Can Restore Its Sense of Peoplehood

- Assaf Orion on Israel’s War with Hizballah

- Abe Unger on America’s First Jewish Classical School

- Marc Novicoff on Why Elite Colleges Were More Likely to Protest Israel

- Liel Leibovitz on What the Protests in Israel Mean

- Gary Saul Morson on Alexander Solzhenitsyn and His Warning to America

- Adam Kirsch on Settler Colonialism

- Raphael BenLevi, Hanin Ghaddar, and Richard Goldberg on the Looming War in Lebanon

- Josh Kraushaar on the Democratic Party’s Veepstakes and American Jewry

- J.J. Schacter on the First Tisha b’Av Since October 7

- Noah Rothman on Kamala Harris’s Views of Israel and the Middle East

- Avi Weiss on the AMIA Bombing 30 Years Later (Rebroadcast)

- Melanie Phillips on the British Election and the Jews

- Mark Cohn on the Reform Movement and Intermarriage

- Jeffrey Saks on the Genius of S.Y. Agnon

- Shlomo Brody on What the Jewish Tradition Says about Going to War

- Chaim Saiman on the Roots and Basis of Jewish Law (Rebroadcast)

- Elliott Abrams on American Jewish Anti-Zionists

- Andrew Doran on Why He Thinks the Roots of Civilization Are Jewish

- Haisam Hassanein on How Egypt Sees Gaza

- Asael Abelman on the History of “Hatikvah”

- Shlomo Brody on Jewish Ethics in War

- Ruth Wisse on the Explosion of Anti-Israel Protests on Campus

- Meir Soloveichik on the Politics of the Haggadah

- Yechiel Leiter on Losing a Child to War

- Yehoshua Pfeffer on Haredi Service in the Israeli Military

- Joseph Lieberman on American Jews and the Zionist Dream (Rebroadcast)

- Seth Kaplan on How to Fix America’s Fragile Neighborhoods

- Timothy Carney on How It Became So Hard to Raise a Family in America

- Jonathan Conricus on How Israeli Aid to Gaza Works

- Vance Serchuk on Ten Years of the Russia-Ukraine War

- Yehuda Halper on Maimonides the Physician

- Cynthia Ozick on the Story of a Jew Who Becomes a Tormentor of Other Jews

- Yehuda Halper on Guiding Readers to “The Guide of the Perplexed”

- Ray Takeyh on What Iran Wants

- Yehuda Halper on Maimonides and the Human Condition

- Hillel Neuer on How the Human-Rights Industry Became Obsessed with Israel

- Yehuda Halper on Where to Begin With Maimonides

- Our Favorite Conversations of 2023

- Matti Friedman on Whether Israel Is Too Dependent on Technology

- Ghaith al-Omari on What Palestinians Really Think about Hamas, Israel, War, and Peace

- Alexandra Orbuch, Gabriel Diamond, and Zach Kessel on the Situation for Jews on American Campuses

- Roya Hakakian on Her Letter to an Anti-Zionist Idealist

- Edward Luttwak on How Israel Develops Advanced Military Technology On Its Own

- Assaf Orion on Israel’s Initial Air Campaign in Gaza

- Bruce Bechtol on How North Korean Weapons Ended Up in Gaza

- Hay Eytan Cohen Yanarocak on Whether Hamas Doomed Israeli-Turkish Relations

- Michael Doran on Israel’s Wars: 1973 and 2023

- Ethan Tucker on the Jewish Duty to Recover Hostages

- Meir Soloveichik on What Jews Believe and Say about Martyrdom

- Yascha Mounk on the Identity Trap and What It Means for Jews

- Alon Arvatz on Israel’s Cyber-Security Industry

- Daniel Rynhold on Thinking Repentance Through

- Jon Levenson on Understanding the Binding of Isaac as the Bible Understands It

- Yonatan Jakubowicz on Israel’s African Immigrants

- Mordechai Kedar on the Return of Terrorism in the West Bank

- Ran Baratz on the Roots of Israeli Angst

- Dovid Margolin on Kommunarka and the Jewish Defiance of Soviet History

- Shlomo Brody on Capital Punishment and the Jewish Tradition

- Podcast: Dara Horn on Why People Love Dead Jews (Rebroadcast)

- Podcast: Izzy Pludwinski on the Art and Beauty of Hebrew Calligraphy

- Podcast: Joshua Berman on the Traumas of the Book of Lamentations

- Podcast: Meir Soloveichik on Ten Portraits of Jewish Statesmanship

- Podcast: Nathan Diament on Whether the Post Office Can Force Employees to Work on the Sabbath

- Podcast: Yaakov Amidror on Why He’s Arguing That Israel Must Prepare for War with Iran

- Podcast: Liel Leibovitz on the Return of Paganism

- Podcast: Rick Richman on History and Devotion

- Podcast: Yuval Levin on How America’s Constitution Might Help Solve Israel’s Judicial Crisis

- Podcast: Neil Rogachevsky & Dov Zigler on the Political Philosophy of Israel’s Declaration of Independence

- Podcast: Yehoshua Pfeffer on Israel’s Social Schisms and How They Affect the Judicial Reform Debate

- Podcast: Jonathan Schachter on What Saudi Arabia’s Deal with Iran Means for Israel and America

- Podcast: Peter Berkowitz & Gadi Taub on the Deeper Causes of Israel’s Internal Conflict

- Podcast: Jordan B. Gorfinkel on His New Illustrated Book of Esther

- Podcast: Malka Simkovich on God’s Maternal Love

- Podcast: Richard Goldberg on Recent Joint Military Exercises Between America and Israel

- Podcast: Russ Roberts on the Disappointment and the Promise of Prayer

- Podcast: Joshua Berman on Traveling to Biblical Egypt

- Podcast: Elliott Abrams on American Jews and the New Israeli Government

- Podcast: Carl Gershman on What the Jewish Experience Can Offer the Uighurs of China

- Podcast: Benjamin Netanyahu on His Moments of Decision

- Podcast: Maxim D. Shrayer on the Moral Obligations and Dilemmas of Russia’s Jewish Leaders

- Podcast: Ryan Anderson on Why His Think Tank Focuses on Culture and Not Just Politics

- Podcast: Simcha Rothman on Reforming Israel’s Justice System

- Podcast: Michael Doran on Iran’s Growing Military Dominance in the Middle East

- Podcast: Scott Shay on How BDS Crept into the Investment World, and How It Was Kicked Out

- Podcast: Haviv Rettig Gur on Netanyahu, Lapid, and Another Israeli Election

- Podcast: Yoav Sorek, David Weinberg, & Jonathan Silver on What Jewish Magazines Are For

- Podcast: Tony Badran Puts Israel’s New Maritime Borders with Lebanon into Context

- Podcast: George Weigel on the Second Vatican Council and the Jews

- Podcast: Shay Khatiri on the Protests Roiling Iran

- Podcast: Meir Soloveichik on Jerusalem’s Enduring Symbols

- Podcast: Daniel Polisar on the First Zionist Congress, 125 Years Later

- Podcast: Hussein Aboubakr on the Holocaust in the Arab Moral Imagination

- Podcast: Jonathan Schanzer on Israel’s Weekend War against Islamic Jihad

- Podcast: Yair Harel on Haim Louk’s Masterful Jewish Music

- Podcast: Jacob J. Schacter on Why So Many Jewish Soldiers Are Buried Under Crosses, and What Can Be Done About It

- Podcast: Robert Nicholson on the Changing Face of Evangelical Zionism

- Podcast: Daniel Gordis & Asael Abelman on the Personality of the New Jew

- Podcast: Douglas Murray on the War on the West

- Podcast: Jeffrey Woolf on the Political and Religious Significance of the Temple Mount

- Podcast: Zohar Atkins on the Contested Idea of Equality

- Podcast: Steven Smith on Persecution and the Art of Writing

- Podcast: Jon Levenson on the Moral Force of the Book of Ruth

- Podcast: Tony Badran on How Hizballah Wins, Even When It Loses

- Podcast: John Podhoretz on Midge Decter’s Life in Ideas

- Podcast: Motti Inbari on the Yemenite Children Affair

- Podcast: Christine Emba on Rethinking Sex

- Podcast: Shany Mor on How to Understand the Recent Terror Attacks in Israel

- Podcast: Abraham Socher on His Life in Jewish Letters and the Liberal Arts

- Podcast: Ilana Horwitz on Educational Performance and Religion

- Podcast: David Friedman on What He Learned as U.S. Ambassador to Israel

- Podcast: Andy Smarick on What the Government Can and Can’t Do to Help American Families

- Podcast: Aaron MacLean on Deterrence and American Power

- Podcast: Ronna Burger on Reading Esther as a Philosopher

- Podcast: Dovid Margolin on Jewish Life in War-Torn Ukraine

- Podcast: Vance Serchuk on the History and Politics Behind Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine

- Podcast: Ruth Wisse on the Stories Jews Tell

- Podcast: Yossi Shain on the Israeli Century

- Podcast: Michael Doran on the Most Strategically Valuable Country You’ve Never Heard Of

- Podcast: Mitch Silber on Securing America’s Jewish Communities

- Podcast: Jesse Smith on Transmitting Religious Devotion

- Podcast: Matti Friedman on China’s New Haifa Port

- Podcast: Jay Greene on Anti-Semitic Leanings Among College Diversity Administrators

- Podcast: Our Favorite Broadcasts of 2021

- Podcast: Three Young Jews on Discovering Their Jewish Purposes

- Podcast: Annie Fixler on Cyber Warfare in the 21st Century

- Podcast: Victoria Coates on the Confusion in Natanz

- Podcast: Judah Ari Gross on Why Israel and Morocco Came to a New Defense Agreement

- Podcast: Michael Avi Helfand on Jewish Life and Law at the Supreme Court

- Podcast: Nicholas Eberstadt on What Declining Birthrates Mean for the Future of the West

- Podcast: Suzy Weiss on the Childless Lives of Young American Women

- Podcast: Michael Eisenberg on Economics in the Book of Genesis

- Podcast: Elisha Wiesel on His Father’s Jewish and Zionist Legacy

- Podcast: Antonio Garcia Martinez on Choosing Judaism as an Antidote to Secular Modernity

- Podcast: Haviv Rettig Gur on the Jewish Agency in 2021

- Podcast: Yedidya Sinclair on Israel’s Shmitah Year

- Podcast: Peter Kreeft on the Philosophy of Ecclesiastes

- Podcast: Dara Horn on Why People Love Dead Jews

- Podcast: Elliot Kaufman on the Crown Heights Riot, 30 Years Later

- Podcast: Cynthia Ozick on Her New Novel Antiquities

- Podcast: Jenna & Benjamin Storey on Why Americans Are So Restless

- Podcast: Kenneth Marcus on How the IHRA Definition of Anti-Semitism Helps the Government Protect Civil Rights

- Podcast: Nir Barkat on a Decade of Governing the World’s Most Spiritual City

- Podcast: Yehoshua Pfeffer on How Haredi Jews Think About Serving in the IDF

- Podcast: Shalom Carmy on Jewish Understanding of Human Suffering

- Podcast: Dru Johnson on Biblical Philosophy

- Podcast: David Rozenson on How His Family Escaped the Soviet Union and Why He Chose to Return

- Podcast: Matti Friedman How Americans Project Their Own Problems onto Israel

- Podcast: Benjamin Haddad on Why Europe Is Becoming More Pro-Israel

- Podcast: Seth Siegel on Israel’s Water Revolution

- Podcast: Michael Doran America’s Strategic Realignment in the Middle East

- Podcast: Sohrab Ahmari on Why Americans Must Recover the Sabbath

- Podcast: Shlomo Brody on Reclaiming Biblical Social Justice

- Podcast: Christine Rosen on the New Crime Wave and Its Consequences

- Podcast: Jonathan Schanzer on the Palestinians’ Political Mess

- Podcast: Meena Viswanath on How the Duolingo App Became an Unwitting Arbiter of Modern Jewish Identity

- Podcast: Sean Clifford on the Israeli Company Making the Internet Safe for American Families

- Podcast: Mark Gerson on How the Seder Teaches Freedom Through Food

- Podcast: Daniel Gordis on the Israeli Supreme Court’s New Conversion Ruling

- Podcast: Gil & Tevi Troy’s Non-Negotiable Judaisms

- Podcast: Richard Goldberg on How Iran Is Already Testing the Biden Administration

- Podcast: Shany Mor on What Makes America’s Peace Processors Tick

- Podcast: Yehoshua Pfeffer on How the Coronavirus Prompted Him to Rethink the Relationship between Haredim and Israeli Society

- Podcast: Gerald McDermott & Derryck Green on How Biblical Ideas Can Help Bridge America’s Racial Divide

- Podcast: Emmanuel Navon on Jewish Diplomacy from Abraham to Abba Eban

- Podcast: Michael Oren on Writing Fiction and Serving Israel

- Podcast: Joel Kotkin Thinks about God and the Pandemic

- Podcast: Dore Gold on the Strategic Importance of the Nile River and the Politics of the Red Sea

- Podcast: Yuval Levin Asks How Religious Minorities Survive in America—Then and Now

- Podcast: Mark Gottlieb on Rabbi Soloveitchik’s “Everlasting Hanukkah”

- Podcast: Ambassador Ron Dermer Looks Back on His Years in Washington

- Podcast: Richard Goldberg on the Future of Israeli-Saudi Relations

- Podcast: Matti Friedman on the Russian Aliyah—30 Years Later

- Podcast: Daniel Gordis on America, Israel, and the Sources of Jewish Resilience

- Podcast: John Podhoretz on 75 Years of Commentary

- Podcast: Michael McConnell on the Free Exercise of Religion

- Podcast: Ruth Wisse on Five Books Every Jew Should Read

- Podcast: Dan Senor on the Start-Up Nation and COVID-19

- Podcast: Reflections for the Days of Awe

- Podcast: Haviv Rettig Gur on Israel’s Deep State

- Podcast: Ruth Wisse & Hillel Halkin on the Authors Who Created Modern Hebrew Literature

- Podcast: Gil Troy on Never Alone

- Podcast: Jared Kushner on His Approach to Middle East Diplomacy

- Podcast: Ambassador Ron Dermer on the Israel-U.A.E. Accord

- Podcast: Micah Goodman on Politics, Power, and Kingship in Deuteronomy

- Podcast: Michael Doran on China‘s Drive for Middle Eastern Supremacy

- Podcast: Peter Berkowitz on Unalienable Rights, the American Tradition, and Foreign Policy

- Podcast: Wilfred McClay on the Historic Jewish-Christian Rapprochement

- Podcast: Amos Yadlin on the Explosions Rocking Iran

- Podcast: Jason Bedrick on School Choice, Religious Liberty, and the Jews

- Podcast: Meir Soloveichik on the Genius of Rabbi Norman Lamm

- Podcast: Tara Isabella Burton on Spirituality in a Godless Age

- Podcast: Gary Saul Morson on “Leninthink“

- Podcast: David Wolpe on The Pandemic and the Future of Liberal Judaism

- Podcast: Chaim Saiman on the “Zoom Seder“ and Its Discontents

- Podcast: Leon Kass on Reading Exodus and the Formation of the People of Israel

- Podcast: Einat Wilf on the West‘s Indulgence of Palestinian Delusions

- Podcast: Matti Friedman—The End of the Israeli Left?

- Podcast: Yehoshua Pfeffer on Haredi Society and the COVID-19 Crisis

- Podcast: Menachem Wecker on Yoga and Idolatry

- Podcast: Moshe Koppel on How Israel‘s Perpetual Election Came to an End

- Podcast: Michael Doran on Coronavirus in Iran

- Podcast: Yossi Klein Halevi on the Transformation of Israeli Music

- Podcast: Richard Goldberg on the Future of Iran Policy

- Podcast: Rafael Medoff on Franklin Roosevelt, Rabbi Stephen Wise, and the Holocaust

- Podcast: Eugene Kontorovich on the Trump Peace Plan

- Podcast: Mark Gottlieb on Jewish Sexual Ethics

- Podcast: Michael Avi Helfand on Religious Freedom, Education, and the Supreme Court

- Podcast: Joshua Berman on Biblical Criticism, Faith, and Integrity

- Podcast: Ruth Wisse on What Saul Bellow Saw

- Podcast: Daniel Cox on Millennials, Religion, and the Family

- Podcast: Yuval Levin on Rebuilding American Institutions

- Podcast: Neil Rogachevsky on Israeli Electoral Reform

- Podcast: Yuval Levin on the Remarkable Legacy of Gertrude Himmelfarb

- Podcast: Best of 2019 at the Tikvah Podcast

- Podcast: Arthur Herman on China and the U.S.-Israel “Special Relationship”

- Podcast: Walter Russell Mead on Israel and American Foreign Policy

- Podcast: Senator Joseph Lieberman on American Jews and the Zionist Dream

- Podcast: Eugene Kontorovich on America and the Settlements

- Podcast: David Makovsky—What Can We Learn from Israel’s Founders?

- Podcast: Christine Rosen on Thinking Religiously about Facebook

- Podcast: Jacob Howland—The Philosopher Who Reads the Talmud

- Podcast: Dru Johnson, Jonathan Silver, & Robert Nicholson on Reviving Hebraic Thought

- Podcast: Thomas Karako on the U.S., Israel, and Missile Defense

- Podcast: David Bashevkin on Sin and Failure in Jewish Thought

- Podcast: Matti Friedman on Israel, the Mizrahi Nation

- Podcast: Micah Goodman on Shrinking the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict

- Podcast: Jack Wertheimer on the New American Judaism – Part III

- Podcast: Meir Soloveichik on the Meaning of Kashrut

- Podcast: Avi Weiss on the AMIA Bombing Cover-Up

- Podcast: Jack Wertheimer on the New American Judaism – Part II

- Podcast: Jack Wertheimer on the New American Judaism – Part I

- Podcast: Jeremy Rabkin on Israel and International Law

- Podcast: Yehoshua Pfeffer on Haredi Politics and Culture

- Podcast: Mona Charen on Sex, Love, and Where Feminism Went Wrong

- Podcast: Dara Horn on Eternal Life

- Podcast: David Evanier on the Rosenbergs, Morton Sobell, and Jewish Communism

- Podcast: Michael Doran on America’s Standoff with Iran

- Podcast: Daniel Krauthammer on His Father’s Jewish Legacy

- Podcast: Yaakov Katz on Shadow Strike

- Podcast: Annika Hernroth-Rothstein on the Miracle of Jewish Continuity

- Podcast: Menachem Wecker on What’s Wrong with the Jewish Museum

- Podcast: Francine Klagsbrun on Golda Meir—Israel’s Lioness

- Podcast: Jonathan Neumann on the Left, the Right, and the Jews

- Podcast: Matti Friedman on Israel’s First Spies

- Podcast: Dovid Margolin on the Rebbe’s Campaign for a Moment of Silence

- Podcast: Scott Shay on Idolatry, Ancient and Modern

- Podcast: Joshua Berman on Whether the Exodus Really Happened

- Podcast: Daniel Gordis on the Rift Between American and Israeli Jews

- Podcast: Nicholas Gallagher on Jewish History and America’s Immigration Crisis

- Podcast: Special Envoy Elan Carr on America’s Fight against Anti-Semitism

- Podcast: Malka Groden on the Jewish Family and America’s Adoption Crisis

- Podcast: Eugene Kontorovich Explains Congress’s Effort to Counter BDS

- Podcast: David Wolpe on the Future of Conservative Judaism

- Podcast: Michael Doran on America’s Allies and America’s Enemies

- Podcast: Jonah Goldberg on Marx’s Jew-Hating Conspiracy Theory

- Podcast: Ambassador Danny Danon Goes on Offense at the U.N.

- Podcast: A New Year at the Tikvah Podcast

- Podcast: The Best of 2018

- Podcast: Jacob J. Schacter on Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik and the State of Israel

- Podcast: Chaim Saiman on the Rabbinic Idea of Law

- Podcast: Daniel Polisar on Herzl’s “The Menorah”

- Podcast: Yehoshua Pfeffer on Haredi Conservatism

- Podcast: Leon Kass on His Life and the Worthy Life

- Podcast: Clifford Librach on the Reform Movement and Jewish Peoplehood

- Podcast: Michael Doran on Theology, Zionism, and American Foreign Policy

- Podcast: Sohrab Ahmari on Sex, Desire, and the Transgender Movement

- Podcast: Yoram Hazony on the Bible’s Political Teaching

- Podcast: John Podhoretz on the Best and Worst of Jewish Cinema

- Podcast: Jamie Kirchick on Europe’s Coming Dark Age

- Special Podcast: Introducing Kikar – Elliott Abrams on Hamas, Gaza, and the Case for Jewish Power

- Podcast: Ruth Wisse on the Nature and Functions of Anti-Semitism

- Podcast: Jeffrey Saks on Shmuel Yosef Agnon

- Podcast: Samuel Goldman on Christian Zionism in America

- Podcast: Martin Kramer on Ben-Gurion, Borders, and the Vote That Made Israel

- Podcast: Russ Roberts on Hayek, Knowledge, and Jewish Tradition

- Podcast: Yossi Klein Halevi on Moving In and Out of Extremism

- Podcast: Charles Freilich on the U.S.-Israel “Special Relationship”

- Podcast: Jeffrey Salkin on ”Judaism Beyond Slogans”

- Podcast: Erica Brown on Educating Jewish Adults

- Podcast: Mark Dubowitz on the Future of the Iran Deal

- Podcast: Greg Weiner on Moynihan, Israel, and the United Nations

- Podcast: Daniel Polisar on Nationhood, Zionism, and the Jews

- Podcast: Jon Levenson on the Danger and Opportunity of Jewish-Christian Dialogue

- Podcast: Leora Batnitzky on the Legacy of Leo Strauss

- Podcast: Wilfred McClay on America’s Civil Religion

- Podcast: Robert Nicholson on Evangelicals, Israel, and the Jews

- Podcast: Charles Small on ”The Changing Face of Anti-Semitism”

- Podcast: Daniel Mark on Judaism and Our Postmodern Age

- Podcast: Ruth Wisse on the Perversity of Brilliance

- Podcast: Daniel Troy on ”The Burial Society”

- Podcast: Matthew Continetti on William F. Buckley, the Conservative Movement, and Anti-Semitism

- Podcast: Jonathan Sacks on Creative Minorities

- Podcast: Elliott Abrams on ”Dictatorships and Double Standards”

- Podcast: Jay Lefkowitz on His Life in the Arena

- Podcast: Michael Doran on America’s Middle East Strategy

- Podcast: Gabriel Scheinmann on Bombing the Syrian Reactor

- Podcast: Elliott Abrams on His Calling and Career

- Podcast: Jeffrey Bloom on Faith and America’s Addiction Crisis

- Podcast: Gil Student on the Journey into Orthodoxy

- Podcast: Meir Soloveichik on ”L’Chaim and Its Limits”

- Podcast: Michael Makovsky on Churchill and the Jews

- Debating Zionism: A Lecture Series with Dr. Micah Goodman

- Podcast: Neil Rogachevsky on the Story Behind Oslo

- Podcast: Mark Gottlieb on Jewish Education

- Podcast: Mitchell Rocklin on Jewish-Christian Relations

- Podcast: Liel Leibovitz on the Jewish Poetry of Leonard Cohen

- Podcast: Ruth Wisse on Tevye the Dairyman

- Podcast: Samuel Goldman on Religion, State, and the Jews

- Podcast: Leon Kass on the Ten Commandments

- Podcast: Ruth Wisse on Cynthia Ozick’s ”Innovation and Redemption”

- Podcast: Yossi Klein Halevi on Ze’ev Jabotinsky’s “The Iron Wall“

- Podcast: Tevi Troy on the Politics of Tu B’Shvat

- Podcast: Jay Lefkowitz & Mitchell Rocklin on the Jewish Vote

- Podcast: Yuval Levin on the Long Way to Liberty

- Podcast: Ruth Wisse on Sartre and Anti-Semitism

- Podcast: Edward Rothstein on Jerusalem Syndrome at the Met

- Podcast: Matthew Continetti on Irving Kristol’s Theological Politics

- Podcast: Meir Soloveichik on King David

- Podcast: R.R. Reno on ”Faith in the Flesh”

- Podcast: Arthur Herman on Why Everybody Loves Israel

- Podcast: Peter Berkowitz on a Liberal Education and Its Betrayal

- Podcast: Meir Soloveichik on Rembrandt, Tolkien, and the Jews

- Podcast: Yoram Hazony on Nationalism and the Future of Western Freedom

- Podcast: Jason Bedrick on Jewish Day Schools and School Choice

- Podcast: Allan Arkush on Ahad Ha’am and “The Jewish State and Jewish Problem”

- Podcast: Bret Stephens on the Legacy of 1967 and the U.S.-Israel Relationship

- Podcast: Jay Lefkowitz on Social Orthodoxy

- Podcast: Norman Podhoretz on Jerusalem and Jewish Particularity

- Podcast: Michael Doran on Western Elites and the Middle East

- Podcast: Ruth Wisse on Campus Anti-Semitism

- Podcast: Meir Soloveichik on ”Confrontation”

- Podcast: Yuval Levin on Religious Liberty

- Podcast: Elliott Abrams on Israel and American Jews